The species we work with

Thanks to Garry Ogston, Gemma Bauld and Grace McNicholas and Morna McGuire for writing the summaries!

Freshwater (or largetooth) sawfish Pristis pristis

by Gary Ogston

The largetooth sawfish (Pristis pristis) can be found across the globe, and consists of four separate sub populations; the Western Atlantic, Eastern Atlantic, Eastern Pacific, and Indo-West Pacific (including northern Australia – spanning the Kimberley to Cape York Peninsula). The species was once considered common across many of these sub populations but has unfortunately undergone drastic population reductions. The largetooth sawfish is now thought to be locally extinct in many regions, and as such is listed as Critically Endangered under the IUCN Red List. The Kimberley region in north-western Australia represents one of the last intact nurseries for the largetooth sawfish, however even within Australia the species is threatened and listed as Vulnerable under Australia’s EPBC Act.

The species is biologically fascinating, both in appearance, due to its large rostrum (averaging between 17 and 24 teeth per side) which is used for predation and defence, and also in its ability to tolerate a wide range of salinities, from freshwater to saltwater. The largetooth sawfish will spend the first three to four years of its life within freshwater systems growing to a length of approximately 3–4 m, before then migrating into the estuarine and marine environments where they reach over 6m in length as an adult. Within the freshwater systems, the diet of the largetooth sawfish consists primarily of species found in the lower water column or benthic environment, such as the blue-catfish (Neoarius graeffei), and detritus.

Fun Facts!

- Did you know? Largetooth sawfish are ovoviviparous; meaning the young develop inside an egg case but remain within the body of the mother until they are ready to hatch, before then being born as live young!

- Did you know? Unlike bony fish, sawfish have no swim bladders and instead rely on large oil-filled livers to help with buoyancy!

Dwarf sawfish Pristis clavata

by Gemma Bauld

The Dwarf sawfish (Pristis clavata) is a species of sawfish that can reach at least 3.2 m in length. It is greenish-brown above and white underneath with gill opening on its underside. Like other sawfish species it has a toothed rostrum. The Dwarf sawfish is found within sand and mud flats associated with close proximity to mangroves in shallow coastal and estuarine waters of northern Australia in the Northern Territory, Queensland and Western Australia. Dwarf sawfish are viviparous (giving birth to live young), with litter sizes unknown but are assumed to be similar to other Pristis species with an average of approximately seven pups per litter. Juveniles are estimated to be between 60–81 cm at the time of birth, and males of the species reaching maturity at eight years old, and a length of 2.5–2.6 m. It is estimated that the Dwarf sawfish have longevity of up to 34 years. Dwarf sawfish in Western Australian waters have been found to occupy restricted areas of habitat. They move up to 10 km during each tide cycle, staying within inundated mangrove forests during high tide and moving out a few kilometres on the low tide. Individuals were found to return to within 100 m of their previous high tide resting sites demonstrating repeated use of habitat. Even large animals frequently occupy habitats less than 2m deep. Current major threats to the Dwarf sawfish include getting their toothed rostra stuck in fishing nets in shallow waters in which they inhabit. Historically their rostra were also collected and traded. However, from 2009, this species was protected from all commercial and recreational use and trade in Australia. The Dwarf sawfish is currently listed as endangered on the IUCN Red List.

References:

The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species

Green sawfish Pristis zijsron

by Gemma Bauld

The Green sawfish (Pristis zijsron) is a species that can grow to 5–7 m in length and is possibly the largest sawfish. They are greenish-brown or olive above and pale to white underneath, with gill openings on its underside. Like other sawfish species it has a flattened head and an elongated snout with uneven-spaced teeth along each side. The Green sawfish in Australia used to be found as far south as Sydney, however its range is now limited to northern Australia (Queensland, Northern Territory and Western Australia). The Green sawfish is also found in the Indo-West Pacific from southern Africa to the Red Sea, Persian Gulf, southern Asia, Indo-Australian archipelago, east Asia and as far north as Taiwan and southern China. They generally inhabit shallow water in coastal and estuarine areas in close proximity to mangrove shorelines. Green sawfish are viviparous (giving birth to live young), with litters being approximately 12 pups. Juveniles are estimated to be approximately 76 cm at the time of birth, and reaching 3.4–3.8 m at maturity at nine years of age. A maximum age for this species is greater than 50 years. Current major threats to the Green sawfish include getting their toothed rostra stuck in fishing nets in shallow waters in which they inhabit. Historically their rostra, fins and meat were also collected and traded locally and internationally, however, this species is now protected from all commercial and recreational use and trade, although difficult to enforce in some countries. The Green sawfish is currently listed as critically endangered on the IUCN Red List.

References:

Simpfendorfer, C. 2013. Pristis zijsron. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2013: e.T39393A18620401. link

Department of the Environment (2017) Pristis zijsronin Species Profile and Threats Database, Department of the Environment, Canberra. link

Narrow sawfish Anoxypristis cuspidata

by Barbara Wueringer

The Narrow sawfish Anoxypristis cuspidata is the only species in its genus. Amongst commercial fishers the species is often known as ‘Slimys’, as juveniles do not develop dermal denticles until about 1.1 m long. The dermal denticles or skin teeth are what gives the skin of sahrks and rays its sandpaper like appearance. Narrow sawfish are the species of sawfish found most offshore, in clearer waters. They have very large eyes and have been found to feed on fast moving species such as squid.

Narrow sawfish are the fastest reproducing species of sawfish, as they reach sexual maturity at about 2–3 years of age. Because of this, Narrow sawfish are still the most common species of sawfish in Australia, and appear to be still abundant on the east coast of Queensland as well as in the Northern Territory, the Gulf of Carpentaria and Western Australia. They are easily distinguished form the three Pristis species, as Narrow sawfish have flat rostral teeth. It is important to mention that Narrow sawfish do not deal well with being caught and handled so if you catch one be sure to release it as quickly as possible.

Narrow sawfish are listed as Endangered on the IUCN Red List of Endangered Species, and in Australia they are listed as Migratory under the EPBC Act and also protected under various state legislations.

References

D’Anastasi, B., Simpfendorfer, C. & van Herwerden, L. 2013. Anoxypristis cuspidata (errata version published in 2019). The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2013: e.T39389A141789456. https://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2013-1.RLTS.T39389A141789456.en. Downloaded on 19 February 2020.

Freshwater whipray Urogymnus dalyensis

by Morna McGuire

The freshwater whipray is the only species of Australian stingray to live exclusively in fresh and estuarine waters. It was first discovered in the Daly River, Northern Territory, giving rise to its epithet: dalyensis. Since then, freshwater whiprays have been documented in at least 10 northern Australian rivers, suggesting they are endemic to the region. As bottom-dwelling species, feeding on small fish and shrimps, they are usually distributed at depths of 1–4 m.

What do they look like?

The main body (pectoral fin disc) of freshwater whipray is distinctively apple-shaped, being as wide as it is long. Projecting from this disc is an obtuse snout, which tapers to a pointed tip. The colouration of its dorsal surface is grey-brownish, though darkens towards the tail. Contrastingly, its ventral colouration is banded: brown spots separate the white centre from the brown margins. Its tail is whip-like (long and thin), often measuring double the disc length. The tail bares a single serrated venomous spine, likely used for defence.

Freshwater whiprays are easily confused with two other ray species: giant freshwater stingray (Himantura chaophyraya) of South-East Asia and estuary stingray (Dasyatis fluviorum) of eastern Australia. However, both molecular and morphological comparisons confirm that they are separate species. For example, the tail of freshwater whipray lacks the ventral skin-fold typical of other ray species.

Although freshwater whiprays are regarded of Least Concern (IUCN Red List), very little is actually known about their ecology. How large is the population? At what age are they sexually mature? SARA’s research on this species is therefore integral to its survival, by informing fishing management practices and conservation efforts.

Fun fact!

Freshwater whiprays are fully committed to catching their prey; they may charge up riverbanks so fast that they breach themselves!

References:

Last, P. R., Stevens, J. D. (2009). Sharks and Rays of Australia. Edition 2. CSIRO Publishing.

Last, P. R., & Manjaji-Matsumoto, B. M. (2008). ‘Himantura dalyensissp. nov., a new estuarine whipray (Myliobatoidei: Dasyatidae) from northern Australia’. Descriptions of new Australian Chondrichthyans. CSIRO Marine and Atmospheric Research, 22, 283-291.

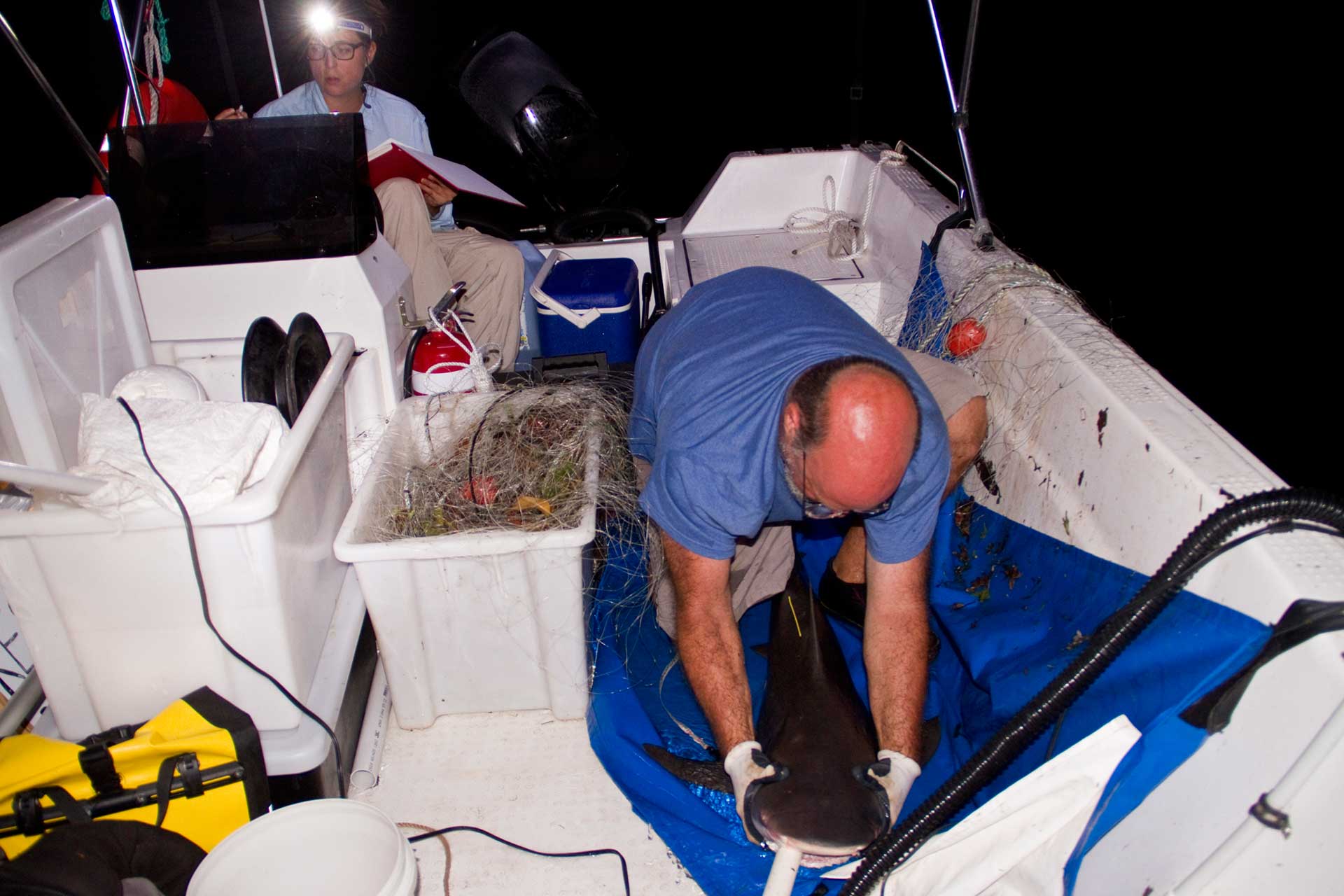

Bull shark Carcharinus leucas

by Garry Ogston

The bullshark (Carcharhinus leucas) is found in warm temperate and tropical waters around the globe, including countries such as Australia, India, Ecuador and the United States of America. The species is listed as Near-Threatened under the IUCN Red List and faces several threats including recreational and commercial fisheries with commercial fisheries globally being driven by the demand for shark fins, liver oil and meat, however it is also regularly caught as by-catch. The species is also threatened by habitat modification, particularly of nursery grounds e.g. estuarine and freshwater systems. Within Australia the bullshark is not protected and is able to be caught for both recreational and commercial fisheries. Several regions of Australia however, have imposed size limits to reduce the threat of overfishing mature specimens.

Although common in marine and estuarine waters, it is only one of a few species of shark that can tolerate long periods in freshwater (e.g. also see river sharks Glyphis spp.), allowing it to penetrate large distances upstream. Pregnant females migrate to the estuarine, freshwater regions to give birth, with the juveniles utilising these areas as nursery grounds. When born, the bull sharks measure between 0.5 m and 0.8 m, before maturing at approximately 1.5–2.2 m for males and 1.8–2.3 m for females. A full grown adult bull shark can reach over 3 m in length. As the bull shark matures it also diversifies its diet, consuming a range of prey species from turtles to birds, teleost fishes and elasmobranchs, and even crustaceans.

Fun Facts!

- Did you know? Bull sharks possess organs known as the ampullae of Lorenzini which act as electroreceptors. These organs are “jelly” filled pores that help detect electrical fields within the water

- Did you know? Bull sharks are not always at the top of the food chain and get predated on by other bull sharks, Orca’s, and even crocodiles!

Winghead shark Eusphyrna blochii

by Grace McNicholas

The Winghead Shark (Eusphyra blochii) is found around the Indo-West Pacific continental shelf. Found in shallow coastal waters, wingheads feed on/near the bottom, with a diet consisting of crustaceans, cephalopods and small fish. Growing to a maximum total length of just 186 cm, they are smallest of all hammerhead species. Being the smallest species, their characteristic elongated head or ‘cephalofoil’ also has the highest width to body length ratio of all hammerheads. It can reach nearly 50% of their total body length. Males and females reach maturity at around 108 cm and 120 cm respectively, and both sexes have a distinct seasonal reproductive cycle, breeding once a year. Females give birth to live young in February/March in litters of 6–25 pups, with new-borns measuring approximately 45 cm.

Unfortunately, winghead sharks are impacted by coastal gillnet fisheries, as their slender elongated heads are easily caught in a range of gillnet mesh sizes. They have also been heavily exploited for their fins and meat. Over the last three generations it is estimated the global population has declined by at least 50%. These declines are most pronounced in areas with intense coastal fishing such as Indonesia and other Asian countries, where reports of wingheads in landing surveys have become less and less common. As a result, Eusphyra blochii are now listed as globally Endangered on the IUCN Red List. However, in Australia, winghead populations are still thought to be relatively healthy due to much lower bycatch levels in the better managed Australian gillnet and trawl fisheries. Although the Australian population is currently only listed as Least Concern, they may still be at risk due to their patchy distribution.

References:

Chin, A, et al. (2017). Crossing lines: a multidisciplinary framework for assessing connectivity of hammerhead sharks across jurisdictional boundaries. Nature Publishing Group, (April), Nature Publishing Group., pp.1–14. [Online] Available at: doi:10.1038/srep46061.

Compagno, LJ. (1984). FAO species catalogue. Vol. 4. Sharks of the world. An annotated and illustrated catalogue of shark species known to date. FAO Fisheries Synopsis No. 125, Volume 4, Part 1.

Sainsbury, KJ, Kailola, PJ, and Leyland, GG. (1984). Continental Shelf Fishes of Northern and North-western Australia, an Illustrated Guide. (Clouston and Hall: Canberra.)

Smart, JJ.and Simpfendorfer, CA. (2016). Eusphyra blochii. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. [Online]. Available at: doi:org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2016- 1.RLTS.T41810A68623209.en.

Stevens, JD and Lyle, JM. (1989). Biology of three hammerhead sharks (Eusphyra blochii, Sphyrna mokarran and S. lewini) from Northern Australia. Marine and Freshwater Research, 40, pp.129–146. [Online]. Available at: doi:10.1071/MF9890129.