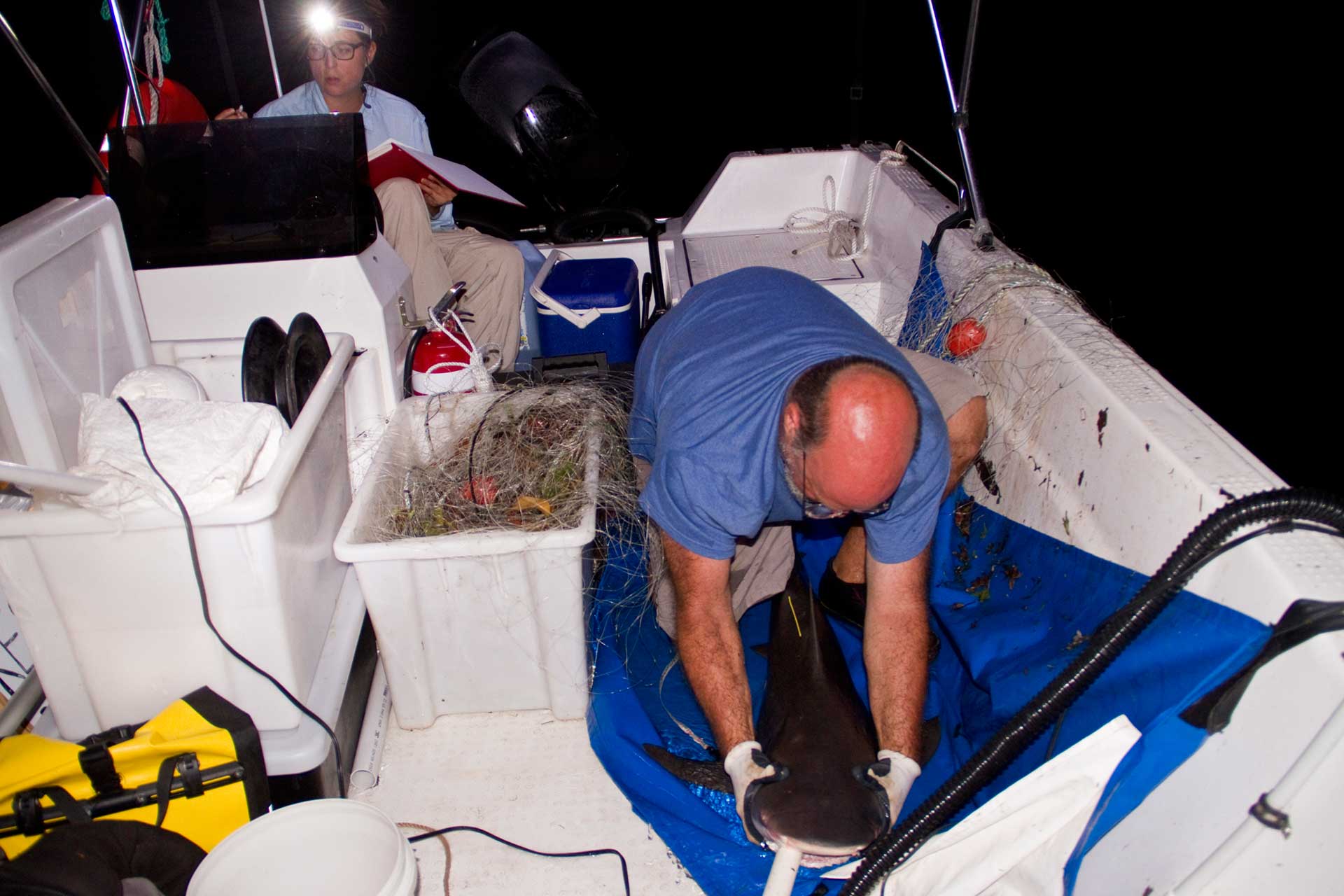

A Green Sawfish with its rostrum amputated (Pic: David Morgan)

The cruel act of amputating distinctive sawfish rostra for trophies should be afforded the same attention as the poaching of body parts from other endangered species like rhinos, a Murdoch University researcher has said.

Associate Professor David Morgan from the Freshwater Fish Group & Fish Health Unit said sawfish protection needed better enforcement globally and the conservation value of sawfish should be actively promoted.

Available evidence suggests sawfish die a lingering death after rostrum removal, he said in an article published in the Fisheries journal.

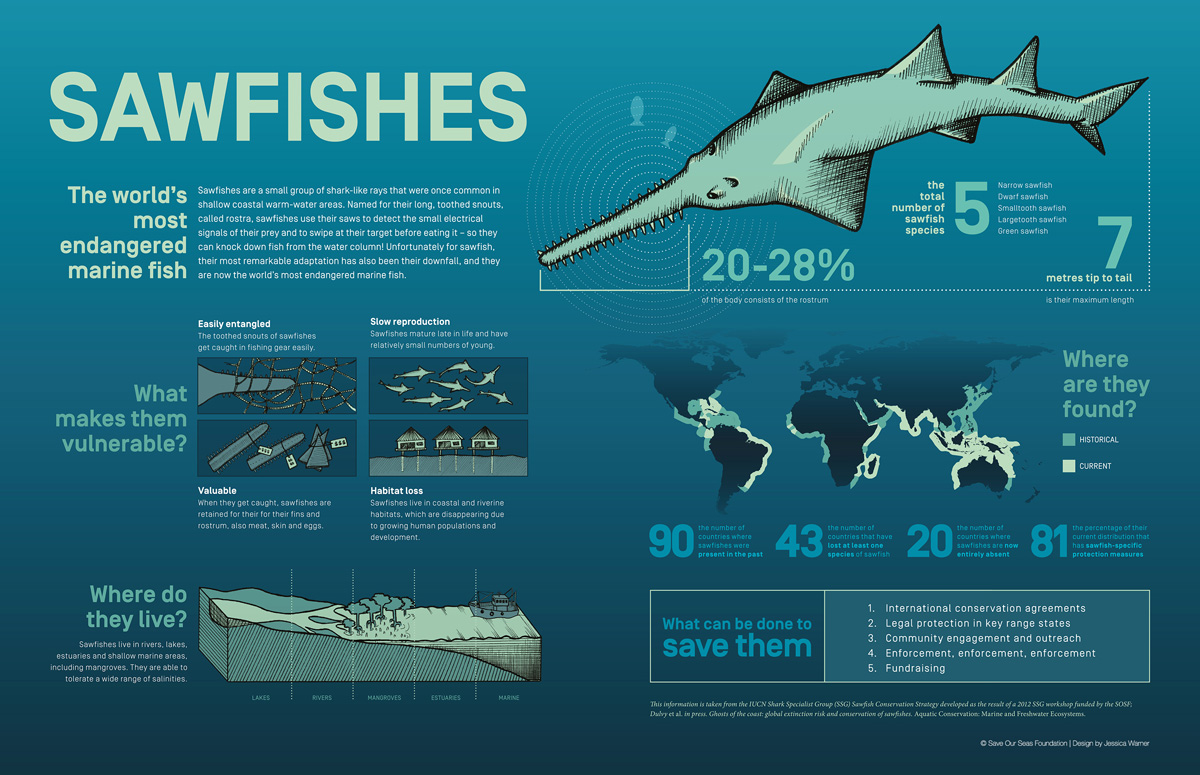

Their rostra – the chainsaw-shaped extension that distinguishes the fish and gives it its name – are used to sense, forage for and capture their prey of crustaceans and small fish.

“Sawfish forage on the riverbed and sense prey via the electrosensitive pores on their rostra,” explained Dr Barbara Wueringer, who co-authored the study.

“They then slash their rostrums to stun or impale their food. They also use the rostrums to protect themselves from predators.”

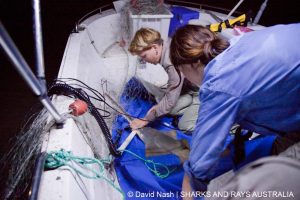

Professor Morgan and his team studied the behaviour of a Green Sawfish found in the Ashburton River after its rostrum had been illegally amputated. They tagged it and observed changes in movement patterns and habitat use compared to similarly sized sawfish with rostra intact.

“We found that it ranged more widely, perhaps in order to source ‘easy prey’ or avoid attacks by predators, than other tagged sawfish of a similar size with rostra intact,” he said.

“After 75 days the fish was no longer detected and may have either emigrated outside the detection range or, more likely, it will have perished because emigration occurred infrequently for other tagged sawfish of that size.”

At a later date, Professor Morgan also captured and tagged a Freshwater Sawfish with a partially severed rostrum contained in an isolated freshwater pool in the Fitzroy River.

He said it was severely emaciated and its damaged rostrum had impacted its ability to effectively forage.

“It was detected by our loggers for 10 days and not thereafter. In comparison, two other similarly sized individuals tagged in the same pool at the same time were detected for several months. This supports our assumption that the injured sawfish died in the pool.”

Professor Morgan said the decline of sawfish due to fishing pressure was exacerbated by humans removing sawfish rostra.

“This undoubtedly negatively impacts survival rates of those fish,” he added.

“Most amputations in northern Australia are from the last few decades.

“The few remaining human population centres that have sawfishes inhabiting their local waters must address this destructive phenomenon, and sawfish protection needs better enforcement globally.”

The Fisheries paper can be read here.