A rare insight into the habitat requirements of large Aussie sawfish

By Barbara Wueringer

Sawfish are very unique creatures, which sometimes poses problems when working with them. The saw of a large sawfish can easily be one the biggest safety hazard you will face during fieldwork. But these animals have another adaptation that has made it difficult to attach tags to them. As the animals often come into shallow waters they have the ability to loosen up their dorsal fins, allowing the fins to fall on the side.

When I worked with captive largetooth sawfish (locally in Australia known as freshwater sawfish) Pristis pristisa decade ago, I realized that in situations that I interpreted as likely stressful for the animals, their two dorsal fins would not stay upright anymore. In captivity these situations included water changes where the water levels in the tanks were first dropped and again raised.

In the wild, when juvenile sawfish venture into shallow waters of 20 cm depth or less, they could easily fall prey to terrestrial predators such as wedgetail eagles, which can reach a wingspan of 2.8m and are commonly encountered in the outback, and near rivers in Northern Australia. This means that it might not be stress, but the low water levels that caused the fins to drop!

The floppy fins pose some difficulties to attaching satellite tags to the dorsal fins of sawfish. The last time that sawfish in Australia, according to our knowledge, were tagged with satellite tags was in 2008 (Stevens et al. 2008). The authors tagged 7 sawfish (5 P. clavataand 2 P. zijsron) with SPOT tags that were bolted to the tip of the dorsal fins of sawfish. These tags are commonly used on sharks, and they can only connect to a satellite and send a location point when the dorsal fin breaks the surface. Additionally one pop-up satellite archival tag was put on another P. clavata. While the PAT tag provided depth data and popped off from the animal after 49 days within a few km of the tagging location, the SPOT tags only provided a handful of locations each (Stevens et al. 2008).

Dr Wueringer holds a towed SPOT-253 tag from Wildlife computers that has been attached to a sawfish. Note the first dorsal fin of the animal falling to the side.

Since then, satellite tagging of sawfish has come a long way, and thankfully with the information provided by our American colleagues, our tagging has been more successful. They successfully trialled the methods of attaching towed tags to large smalltooth sawfish Pristis pectinata (for more info see Carlson et al. 2014, Guttridge et al. 2015, Papastamatiou et al. 2015) and shared their set up with us.

The next challenge for us was to find sawfish that were healthy (i.e. did not have their saws amputated) and large enough to tow the tags. In March 2019 it finally all came together and we were able to deploy two of our towed SPOT (smart position and temperature) tags! The first one was deployed on a 280cm long, and likely sexually mature female, Dwarf sawfish Pristis clavata and within 24 hrs the second tag was deployed on a 300cm long juvenile green sawfish Pristis zijsron.

One tag detached after about 3 months while the other one stopped sending location data 10 months after deployment. However, while the analysis and project is still ongoing, we can already see that the data we have received is amazing.

One of the most important outcomes of the tag deployments is that we were working with a commercial fisher on this expedition, who now knows how to deploy tags for us and is excited to do so. So we hope that the next tags won’t have to wait another 3 years to be deployed, as we all work together to find large sawfish.

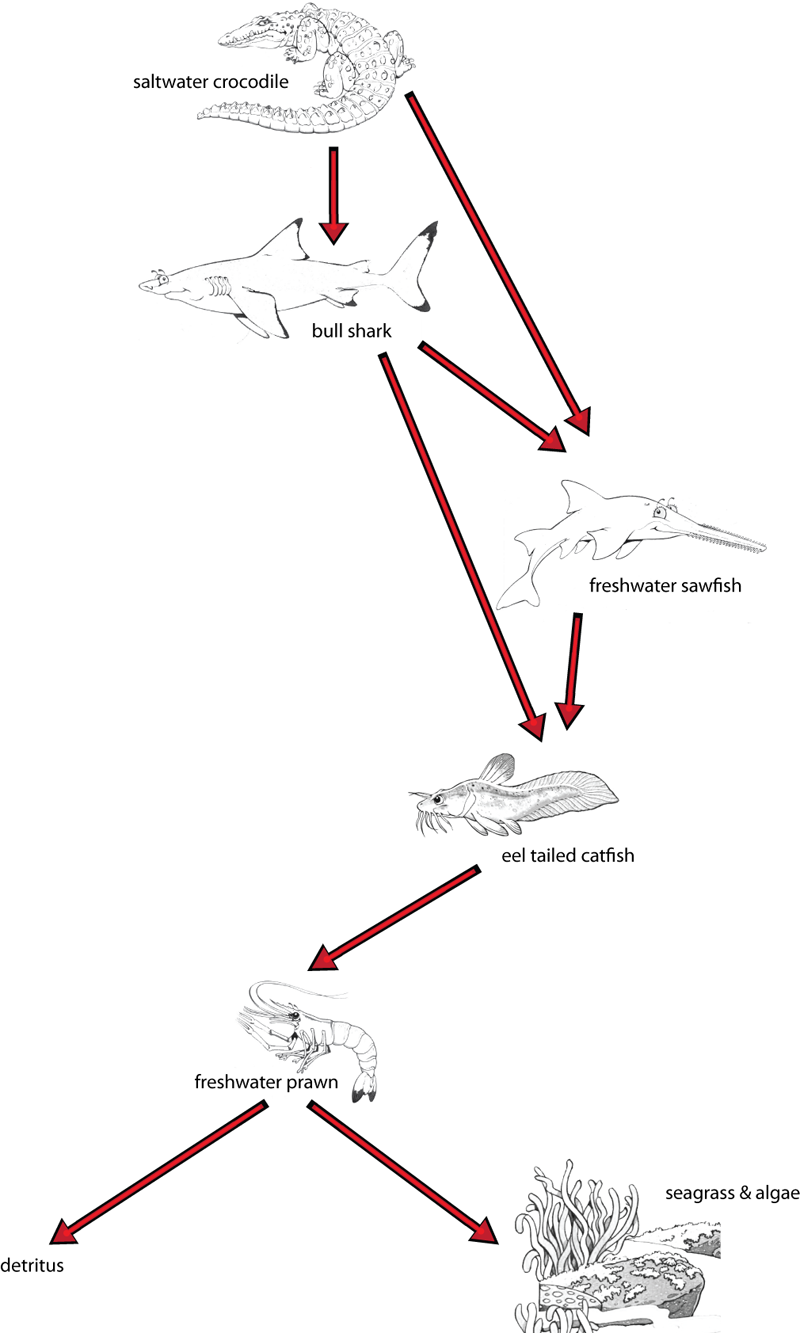

This image shows a subset of the raw location fixes that we received from our tagged green sawfish. Each dot represents a location fix. Location fixes can have errors (including land based locations), especially when a tag does not surface long enough to send its data to the satellite.

This project has received funding by the Save Our Seas Foundation, the Seaworld Research and Rescue Foundation Inc., the Shark Conservation Fund and the Sydney Aquarium.

This blog post was originally written for the Save Our Seas Foundation. you can access the original here.

References

Carlson, J. K., Gulak, S. J. B., Simpfendorfer, C. A., Grubbs, R. D., Romine, J. G. and Burgess, G. H. (2014). Movement patterns and habitat use of smalltooth sawfish,Pristis pectinata, determined using pop-up satellite archival tags. Aquatic Conserv. Mar. Freshw. Ecosyst.24, 104-117.

Guttridge, T. L., Gulak, S. J., Franks, B. R., Carlson, J. K., Gruber, S. H., Gledhill, K. S., Bond, M. E., Johnson, G. and Grubbs, R. D. (2015). Occurrence and habitat use of the critically endangered smalltooth sawfish Pristis pectinata in the Bahamas. J Fish Biol87, 1322-1341.

Papastamatiou, Y. P., Dean Grubbs, R., Imhoff, J. L., Gulak, S. J. B., Carlson, J. K. and Burgess, G. H. (2015). A subtropical embayment serves as essential habitat for sub-adults and adults of the critically endangered smalltooth sawfish. Global Ecology and Conservation3, 764-775.

Stevens, J. D., McAuley, R. B., Simpfendorfer, C. A. and Pillans, R. D. (2008). Spatial distribution and habitat utilisation of sawfish (Pristis spp) in relation to fishing in northern Australia. 26.