Delta Downs Expedition (Part Two) by Liz Xanthopoulos

by Barbara | May 9, 2017 | Blog | 0 comments

by Liz Xanthopolous, A visitor to this time

Home became the banks of the river, which had a 3 metre steep elevation from the water, so we were completely safe from said Jurassic creatures creeping up and snatching one of us while we slept. We found a large patch of dirt to set up camp next to a little pond, surrounded by long green grass, tall brown termite mounds as far as the eye could see, and some trees and bushes. To add to the ambiance were dried up piles of cow poop all over the place that we shoveled out of the way. Our new little home was known as Snake Creek, which lived up to its name when Barbara nearly stepped on a Brown Snake one night while checking the tide, and after we came across a few more around camp I was very quickly forced to overcome my fear of snakes. The scenery around us was vast, open and never-ending. It was nature in all its glory. Wild and beautiful, and so silent. Every sunrise and every sunset we were treated to the most beautiful shades of pink and orange in our sky, and every night the brightest stars I’ve ever seen would come out and put on a show.

Our tagging shifts were twice a day, in three person teams. The morning shift, my shift, usually started at about 5 am, until about 11 am. It was still dark when we’d get out on the water, so we had to use our headlamps and the boat’s spotlight to get our work done. Crocs are most active at night, it’s their favourite time to hunt so they’re out and about. We made sure we used the boats spotlight to scan the banks of the river, for navigating of course but also to make sure we were constantly monitoring our surroundings. Their eyes reflect light so we would often see tiny little red eyes looking at us in the dark. To be honest, even though croc safety was emphasised and mentioned in all the paperwork, I had no idea how big a factor they would actually be, but after arriving at Snake Creek, talking to the rangers and taking into account of course Barbara’s previous experiences in these areas, I knew we would have to take procedure seriously and stay focused to make sure everyone on board was as safe as possible at all times.

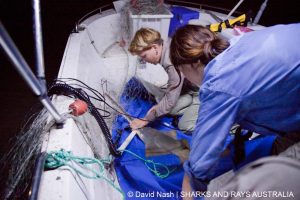

We would begin our sessions by setting up four drum lines and two gill nets, and routinely checked and moved them to different spots along the river to better our chances of catching something. It did get easier to work after the sun came up and we had more light, and it was still early enough so the heat wasn’t as scorching as it would be later in the day, but nevertheless the shifts were still physically demanding. Lifting and throwing anchors, reeling in and then releasing the nets, pulling out and releasing any bycatch over and over and over again, all the while making sure we weren’t hanging over the side of the boat or sticking our hands in the water to avoid tempting the crocs stalking us from beneath the surface. I think even Barbara was surprised at the huge number of jellyfish that were in the river system. Pulling up these 50-metre-long nets that essentially became a wall of jellyfish because there were so many were drifting into the nets became really challenging. I’ve been stung by jellyfish a couple times before while up on the Gold Coast, so their sting wasn’t anything new to me, but it just meant that we had one more thing that we had to be cautious of.

After getting back to camp once our sessions were over, I would usually run straight to our kitchen and shovel down as much food in me as I could to replenish all the energy we’d lost in the morning. I also had a couple of Hydralyte’s a day to make sure I was properly hydrated. After breakfast/lunch we would wash as much mud/sunscreen/fish guts (from the bait) and sweat off us as we could – using nothing more than a quarter bucket of water and a washcloth (hey, it did the job!), change our clothes, and try to stay in the shade to conserve our energy. Walking from our “shower tent” to my swag was an adventure of its own if I dared make the trip barefoot. The path to get to there forced me to walk past the biggest termite mound, and if the ants around there were quick enough to jump on my feet as I crossed through I was in for a hell of a sting.

We would spend the rest of the day listening to music, or the ‘Serial’ podcast one of the marine biologists brought and then discuss it, we’d talk about life or different birds that we’d spot, and collect wood for our fire. After getting dinner ready, having a chat around campfire while eating, and washing up, the evening shift would head out just before sunset for their session, and usually wouldn’t make it back until after midnight. Those of us on the morning shift would try to get to bed early and get a good night’s sleep to be fresh for the morning after. Oh yeah! I forgot to mention – late in the evening it was crucial to put on long sleeves and spray heaps of insect repellent on. I’m not a person that ever gets bit by mosquitoes, but out there, I got mauled. Mozzies and midges everywhere. You could never escape it, and it was bloody frustrating as hell.

I’ll never forget the ray we caught on one of our drum lines. While I was pulling the line up I could feel it getting heavy and I knew we had something, and suddenly a long black slimy tail broke the surface of the water. The first thing I thought was (don’t laugh at me) “oh my god, it’s a snake!” but once I saw the rest of its body I realised it was actually a big ray. We kept the line in its mouth and towed it to the little bank in front of our camp because it was too big and too heavy to lift onto the boat like we normally would’ve. There we checked the gender (it’s a boy!), measured him, took some photos and tagged him. His body was about 1.5 metres wide, so he was a big boy. I had to put my hands in his gills to lift him up so Barbara could get the hook out of his mouth, so I ended up with essentially ray snot on my gloves. I even found myself patting him like a dog, I guess I thought that if he felt my hand he might feel comfort, and he’d know that he’d be OK, because I can only imagine how scared he was. Barbara later identified him as a Freshwater Whip Ray. We caught another one a few days later but he was much smaller.

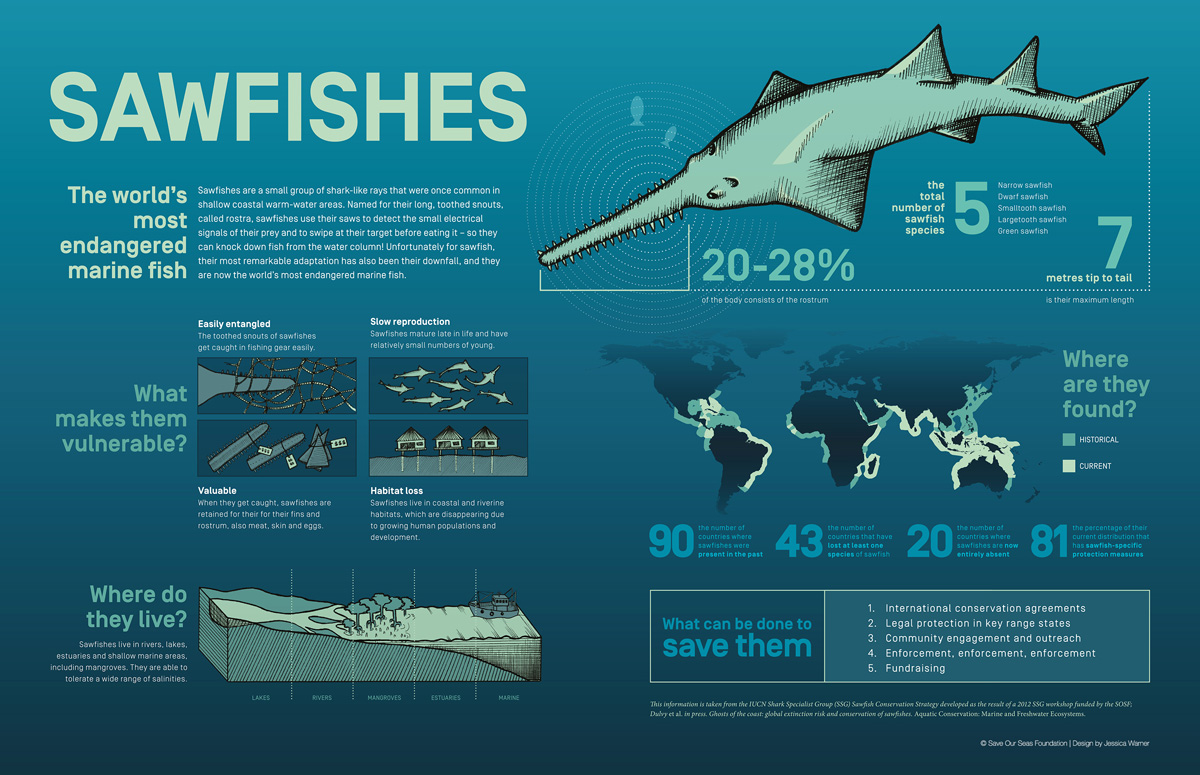

Despite all our hard work, planning, and best efforts, it wasn’t in our fate to encounter the incredible sawfish. All the data we collected will still contribute to SARA’s research, maybe not in the way we hoped but I’m sure we collected more pieces to the puzzle. I remember Barbara telling me that most people become completely captivated by sawfish when they first set their eyes on them because of their strange appearance, and although I missed out on that moment, I did not feel disappointed with my experiences during the expedition. Having the privilege of witnessing the beauty of one of the most untouched locations in the country that only a handful of people have visited, and having the opportunity to participate in an important scientific research expedition with a great group of people far exceeded any expectations I had. And so, after the most amazing 10 days at Snake Creek, it was time to pack up camp and start the two-day trek back to Cairns. We made it all the way to Croydon when we decided to stop for the night at a caravan park and treat ourselves to dinner and a couple of drinks at the local pub. We all walked in and stopped in our tracks when something caught our eye on the wall behind the bar. Two sawfish rostra. Two sawfish rostra hanging on the wall in a pub. Yeah, heartbreaking. But it did bring us back to reality and confirmed to us that everything we just went through won’t be for nothing. There’s still a lot of hard work that needs to be done and the biggest challenge will be changing people’s perceptions and attitudes toward animals, but it can and will be done.

Just like that, after all that time in the middle of nowhere, with no communication with the rest of the world and only the six of us for company, just us vs the wild, we were back in Cairns. It just seemed so loud to me. So loud and so busy, and it took me a couple of days to get used to being surrounded by so many people. I spent a few more days in Cairns exploring, drove down to Mission Beach and Etty Bay to find some Cassowaries, and went over to my beloved Great Barrier Reef for a few dives (I will talk about my love for the Reef in many posts to come), and then it was time to head home. Actual home. Melbourne home. The same night I arrived I was sitting on the couch watching TV when my mum asked me how it felt being home. It felt strange. I caught myself looking over my shoulder and looking around me to make sure nothing was trying to sting me or bite me. It felt strange feeling safe. The Delta Downs expedition was my first real call of the wild, and I’ll hold onto the experiences I had there forever. Without a doubt, there will always be a part of me that’s constantly seeking it out. Even when walking my dog, certain smells or sensations make me feel like if I close my eyes I’m back in Snake Creek sitting around the campfire having a laugh over dinner watching the sun set. Whenever life starts getting a little overwhelming and I get that urge to run away, my mind drifts back to the simpler times of Snake Creek where the only thing I really had to worry about was eating and not being eaten! Just the way nature intended.