SawSearch project update December 2018

We were out in the waters of the Mitchell River, near the Indigenous community of Kowanyama. Every day we would wake at 3am ready for a 4am start of setting nets on the river. After a 7hr sampling session, we’d eat and rest and then run another sampling session in the evening, either hand-lining for freshwater whiprays (last year we had also caught a saw-less sawfish like this), or setting more nets.

The first few days we were only catching small bull sharks, which is fairly stressful when gill netting. Sharks don’t do well in gill nets, but in this part of the river, which is freshwater, many of the sharks we had caught over the last three years had a fungus infection visible on their skin. This meant that we had to be even faster releasing them, otherwise they would struggle.

One morning, we had caught multiple juvenile bull sharks in one net, so many in fact that we were continuously checking the net to get them all out so that we could pull the net without injuring them. When the net was finally retrieved, and we arrived back at the camp, we were greeted by a very angry couple waving paperwork at us (in the middle of nowhere) shouting that they had booked this particular camping spot where we had set up our camp. As we did not want to get in trouble with anyone, and our booking had been made by the local rangers who were on weekend break, we had to move. The move took about 3 hrs, and our new camping spot, the only one providing a safe entrance to our boat, also displayed a stark reminder of the presence of saltwater crocodiles (Figure 1).

Fig. 1: Upon assessment of our second camping spot we found this footprint of a saltwater crocodile Crocodylus porosus. Saltwater crocs can be quite dangerous to humans and a colleague from Australia Zoo estimated the owner of this footprint to be over 5m long. Barbara’s foot is a size 38 European. However, during our time at the camp spot this crocodile would have not been able to lift itself up the steep riverbank because of low tides.

After an afternoon nap, everything changed. We all agreed that our new camping spot was better than the old one, and started over. We became friends with our neighbours. There were no more bull sharks in the net, but sawfish! And we were finally able to deploy our custom-built tags. These tags combine an accelerometer, which records the movement of the rostrum in 3D space, with temperature, light and pressure sensors, in a casing that allows the tags to be mounted on the base of a sawfishes’ rostrum. An acoustic tag allows active tracking of the animal and a VHF tag allows us to find the tag once it has detached.

There are many release mechanism for tags in saltwater and they generally involve corrosion. In freshwater this does not work and so we tested our own ideas of dissolvable string. With the ‘perfect’ lab-tested configuration, the first tag detached upon release of the animal (2 mins into a 3 day deployment). We modified the set up, and the second and third tag released after about 4 hrs. The fourth tag finally stayed on (figures 2,3 and 4).

Fig 2: Sarah O’Hea Miller helps Dr Wueringer to attach the first accelerometer tag to the saw of a juvenile freshwater sawfish Pristis pristis.

Fig 4: A happy SARA team is ready to release this freshwater sawfish, Pristis pristis, with its tag attached.

With a team of four, and three people required on the boat for tracking, it was difficult to take turns going on land, relaxing and preparing food. After close to 30 hrs of tracking the sawfish, with only 3 hrs of sleep, we recovered the tag. Having worked with sawfish for 13 years, this included one of my most memorable moments of fieldwork. As the tag had not been moving for a while, we decided to head to the side of the river where it was located. In order to not scare the sawfish, I beached the boat further upstream, got out and moved to the high bank under which the tag was pinging. The water was clear and I could see the little sawfish with our tag attached to its rostrum hunting baitfish.

One of our field assistants was so impressed by what she had experienced on the expedition that she even ended up with a tattoo of a sawfish (figure 5). Clearly these animals are not only of cultural importance to Indigenous Australians, but to all of us.

Fig 5: One of our volunteer field assistants turned her experiences of the expedition into a permanent memory in the shape of a sawfish tattoo.

This blog post was written by Barbara for the Save Our Seas Foundation. You can access the original here.

written by Nicolas Lublitz and Barbara Wueringer

Sawfish are the stuff of legends: Animals that can grow up to 7 m long and have an extended rostrum (the ‘saw’) loaded with teeth. Old newspaper articles have described them as monsters that lurk in our rivers and oceans and are just waiting to attack people. Quite the opposite is true, as sawfish use their „saw“ skillfully in order to stun and manipulate their fishy prey, not caring for us humans. They are magnificent animals, no doubt.

Anecdotal reports claim that sawfish used to be so plentiful that people in Sudan once used their rostra as fence posts. Additionally, a study from Lake Nicaragua estimated that between 1970 and 1975 around 60,000 – 100,000 animals were caught in the lake by commercial fishers. This was once thought to be their largest population. A survey in 1992 could not find traces of a single individual in the lake.

Today, five extant species are recognized. All are either listed as Critically Endangered or Endangered under the criteria of the IUCN, making sawfishes the most endangered of all the sharks and rays in the world. Four out of those five species can be found in Queensland waters, which are thought to be home to some of their last important populations in the world. With significant global declines for all species, the question arises, if the rivers and coastlines of Queensland are still a stronghold for these animals?

First, we need to engage in a debate about our baseline – how abundant was the species in the past? This search can turn philosophical really quickly. How do we determine a healthy population? What levels do we want the population to return to? Does it need to return to pre-human influence levels or is it enough to keep the population at a level where it can somewhat perform its ecological function? Or is exploitation more important than conservation?

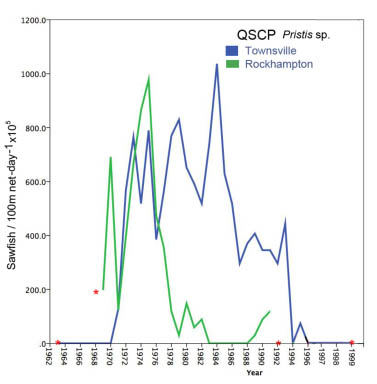

Secondly, we need to determine how much the population of sawfish have declined in Queensland. To answer this, sawfish capture data from the Queensland Shark Control Program (QSCP) was analysed. This program started in 1962 and aims to protect swimmers/surfers from potentially dangerous sharks by utilizing gillnets and baited drum lines. Although no scientific evidence exists that the program actually works, it has been in place for decades.

The data shows that between 1962 and 2016, 1450 sawfish were captured,with 99% of captures occurring in the four most northern areas of Queensland’s East Coast, suggesting the existence of critical habitat. Most animals were caught in the nets and not on drum lines.

An overall decreasing trend in catch rates was observed for two locations where standardized catches could be calculated. However, standardized catch rates from the data set are likely underestimating abundances, as the nets were set up to 500m away from the coast, in deep waters where they often did not reach the bottom. Most sawfish captures occurred near the bottom of the nets.

The facts of this data set make firm conclusions on abundance declines difficult, although it is apparent that the declines have been statistically significant. We need to devote more resources to better understand population trends in Queensland’s sawfishes.

You can access the publication on sawfish catches in the Queensland Shark Control Program here.

This blog post was originally written for the Save Our Seas Foundation. Access the original blog here.

Standardized catch rates for sawfish (fam. pristidae) in gill nets in two separate locations of the Queensland Shark Control Program, 1962 – 2016. Red stars indicate when fishing began and ceased in the respective location.

The next morning, we woke to strong winds and white horses on the river, which up until now had been as flat as a pancake. We later discovered an extreme wind warning had been issued for nearby marine areas, but outside of the reach of even the coastguard this information is not easy to come by. Getting the research vessel out without damaging it against the rocks would be impossible. Additionally, as this river is very shallow, the wind was pushing the surface water downstream, resulting in a prolonged low tide. With no boat ramp, its essential the back wheels of the boat trailer can be reversed into the water at the correct angle so that the boat can be winched on securely. Unable to get the back wheels in deep enough due to the low tide, Barbara suggested accessing a small area on the other side of the river where a commercial fisherman had a semi-permanent camp. Barbara and Julia, who had experience with 4WD, took the Troopie back down the bumpy dirt track. Sitting in our half-dismantled but wind-proof camp and snacking on gingernuts, Annmarie and I waited as the wind howled around us.

Three and a half hours later they returned with bad news. The other area was muddy and soft and with no way to pull the boat out. It was back to the drawing board. The next night we took turns to wake up every hour to check the position of the tide, after marking the sand with numbered increments. My first alarm went off at 1am and after scrabbling around to find my headtorch and pulling on my walking boots, I made my way towards the water’s edge. My heart pounded as I scanned the surrounding area for two glowing red orbs, the infamous sign of crocodile eyes. Phew, no sign of crocs tonight, just the familiar glittering of spider’s eyes sprinkled across the ground. I checked the tide, which was still low, then made a note on our timetable back at camp and tucked myself into my swag until my next check at 5am. A little more confident this time, I headed straight for the shore. Surely, I would find a higher tide? No such luck, the waterline had barely moved.

We discussed our next move over breakfast, which for me obviously involved a good old brew of English Breakfast Tea. The wind had died off and although the tide was still low, we’d have to give it our best shot to get the boat out today. After some skilful driving from Barbara, and some manual re-adjustments from all of us, we finally managed to position the trailer at the exact angle the wheels could go back far enough to get the boat on. A few painstaking hours later and the boat was on the trailer. However, the unevenness of the shoreline meant we couldn’t pull it out without tipping the boat, so back in it went.

Up until now the morale had been pretty high, but the midday sun and exhaustion were starting to get to us all. We agreed it was time for lunch. A can of coke and sandwich later and we were ready to try again. After driving the boat a little upstream, we accessed an area we had previously discounted as there was a large shallow sandbank blocking the boats trajectory to the shore. At first sight we still weren’t hopeful, but with some group perseverance, we managed to guide the boat onto the trailer and winch like crazy! To be honest this part was a bit of an emotional blur and the details are a little foggy. The only thing I do know for sure is I’ll never forget the comradeship and pride we all felt when the back wheels of the trailer finally made it out of the water with the boat firmly attached.

We spent the next night in a campground back in town and were ecstatic over hot showers. We squeezed in one more sampling session in the Norman river (there is a boat ramp!), but despite keeping everything crossed we still didn’t catch any elasmobranchs. As disappointing as this was, unfortunately this is the heart-breaking reality of working with critically endangered species with severely depleted populations. The next day we had arranged to visit the local school to talk about sawfish and the research we were doing. Outreach is an important aspect of SARA and these school visits are a fantastic opportunity to connect what Indigenous kids see when out ‘on country’ with actual science, and maybe even inspire the next generation of biologists and conservationists. The interaction and excitement from these kids was truly heart-warming and gives me great hope for the future.

I’m back in England now, and as I sit here writing this, I can’t help but feel overwhelming proud of myself. SARA expeditions are hardcore, working in some incredibly harsh conditions, with some of the most endangered animals on the planet. From day one of landing in Cairns, to those bucket showers in the outback, this experience has been the most rewarding thing I have ever done; and although I wasn’t lucky enough to see a sawfish, to have even had the opportunity to be involved in a project that could change the fate of future conservation is reward enough. Those two weeks will stay with me forever and it couldn’t be an easier decision for me to sign up for another trip next year.

I’d like to thank Julia and Annmarie for being such enthusiastic, caring team mates and Barbara, the sawfish Goddess herself, for being such a wonderful mentor and friend to all of us.

In August 2018, Sharks And Rays Australia and the Cairns Museum jointly organized a sawfish afternoon at the museum, for National Science Week. Kier Shorey from ABC Far North radio ran a story, and Daniel Bateman wrote an amazing article for the Weekend Post. I am sure that their contributions had lots to do with the huge success of the event, so we would like to thank them for playing such a vital role in helping us reach the public!

More than a month later, we finally finished sampling all the saws from people who responded to the event! This clearly shows that the response was overwhelming and the information collected exceeded our expectations by far!

Here are some of our stats: the Facebook event was viewed 6700 times, and we had 21 people who signed up for it on Facebook, while 100 people were interested. The actual turn out was about 40 people and most of them also went to Dr Wueringer’s talk.

We also had – and this is the most exciting part for SARA – the opportunity to take DNA samples from 48 saws, including 11 saws that were donated to SARA. Moreover, five sightings of live sawfish were submitted to us.

All the DNA samples will be sent to Annmarie Fearing at the University of Mississippi, who will use them for her Masters research project. Many of you met her during the event. The samples will help to identify if and when the genetic diversity held by different species of sawfish decreased. The project also aims to identify which regions globally hold the highest genetic diversity of the different species of sawfish. These regions will then be named as hotspots and should thus be a conservation priority.

For the saws that were donated to SARA we have big plans as well, which we are currently discussing with the Department of Agriculture and Fisheries in Queensland. While we use some saws for our school visits, we want to see the other saws on display in tourist information centres, museums and pubs in Far North Queensland and the Cape York region. Displaying these saws together with information on the conservation of sawfish and where to submit sightings means that these former trophies can become active contributors to sawfish conservation in Queensland!

So with this I would like to thank everybody who made this event possible and who responded to our call and brought their saws in. I would also like to thank Grace McNicholas from York University for helping with the sampling and Annmarie Fearing for involving SARA in her project.

This project is ongoing, so if you have a saw at home that we hve not sampled yet, then please get in touch!

a